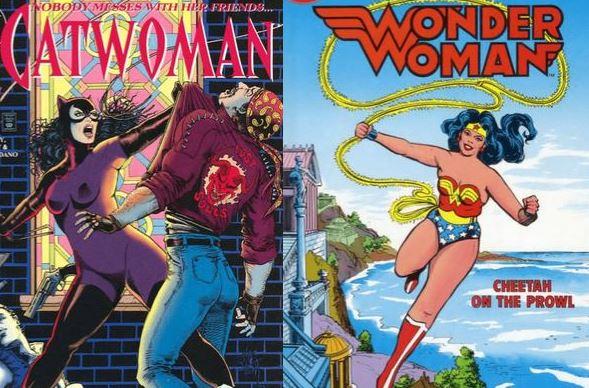

Reworked images by Bulimia.com prove there really isn't any reason that all heroes have to have the same body.

Joe Shuster, the original Superman artist, was fascinated with fitness and bodybuilding. "I tried to build up my body. I was so skinny; I went in for weight-lifting and athletics. I used to get all the body-building magazines from the second-hand stores—and read them . . ." he told one interviewer. Superman initially, then, was a vision of Shuster's ideal body type, a dream of who he wanted to be—muscles, skintight shorts, and all.

It's not a surprise, then, that superheroes have continued to present idealized, impossible body types. The men have bulging muscles (sometimes, as with the Incredible Hulk, parodically bulging muscles). And women have hourglass figures with impossible breasts (in cases like this, literally impossibly so). At least for the main superhero publishers, Marvel and DC, the genre tropes call for women to look like exaggerated inflatables and men to look like steroidal ads for testosterone.

Bulimia.com recently undertook a project which challenges those genre assumptions in some interesting ways. The site took iconic comic book characters and images, and reworked them so that they more closely reflect average American body shapes.

The goal of the project isn't to change comics, or to criticize them for promoting bad body image, according to an interview at HuffPo:

"Rather, our hope here is to show the extent to which superheroes' body types (as is the case with their super-human abilities) are fictional. Our hope is that when viewers see these superheroes visualized in such a manner that they can identify with them, they may feel better about themselves and realize the futility of any comparison between themselves and the fictional universes of Marvel and DC Comics."

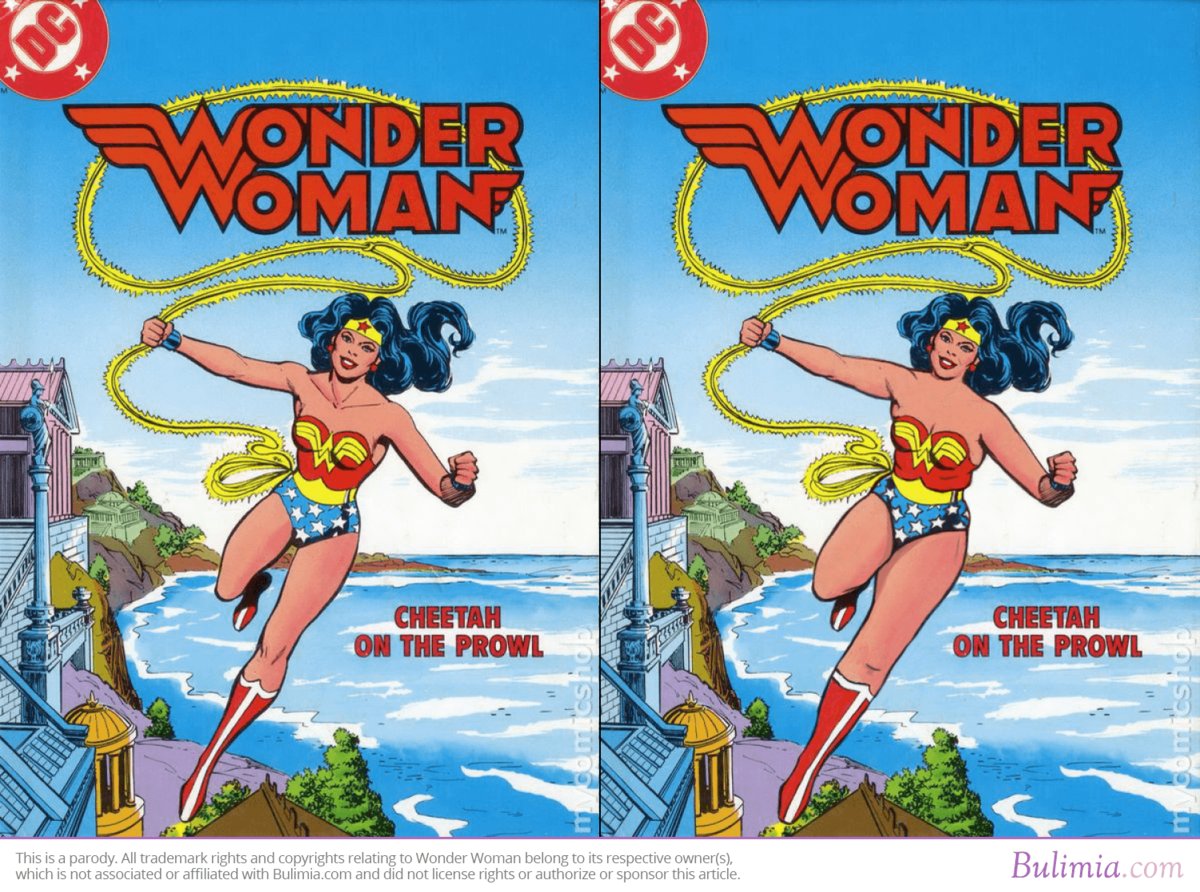

But while that's a worthy goal, the exercise also demonstrates, inadvertently, that for superheroes, different body types sometimes work better. Look at this reworking of Wonder Woman, for instance:

Wonder Woman here is running forward with fists clenched; it's a pose that's supposed to convey power. On the left, though, she's got the typical superhero body type, which means she's extremely thin; her collar bones practically look like they're trying to outrun her. The image on the right, on the other hand, shows a Wonder Woman with actual honest-to-goodness broad shoulders; she looks like she'd really have some force behind it if she hit you. Her physique is more Amazonian—which seems truer to the character.

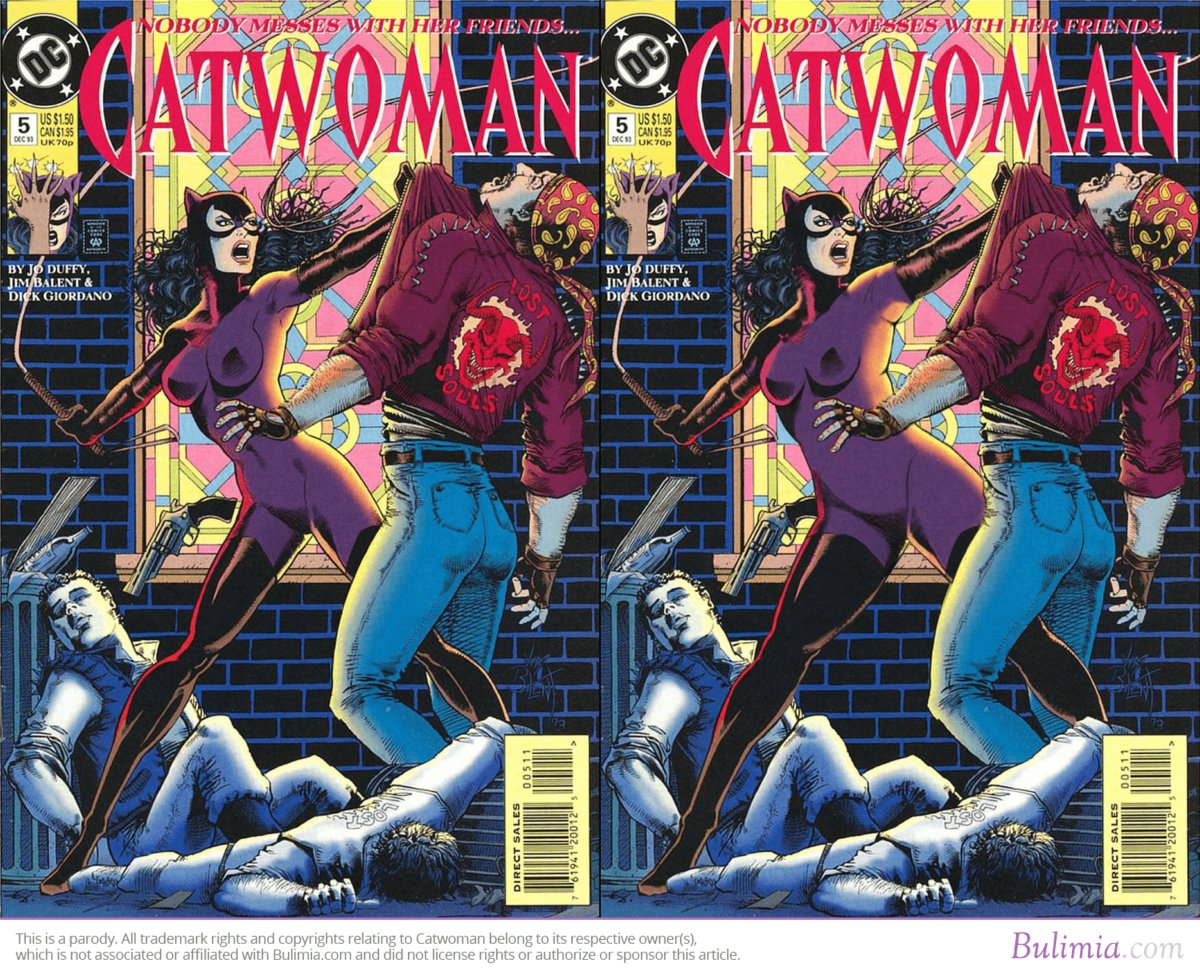

The Catwoman reworking is similarly eye-opening..

The heroine on the left looks thin enough to snap; her breasts are so out of proportion she seems in danger of tipping over backwards. It's the Catwoman on the right who convinces you that she could take this guy out. Even the composition works better; the more reasonable proportions give her enough bulk to dominate the frame.

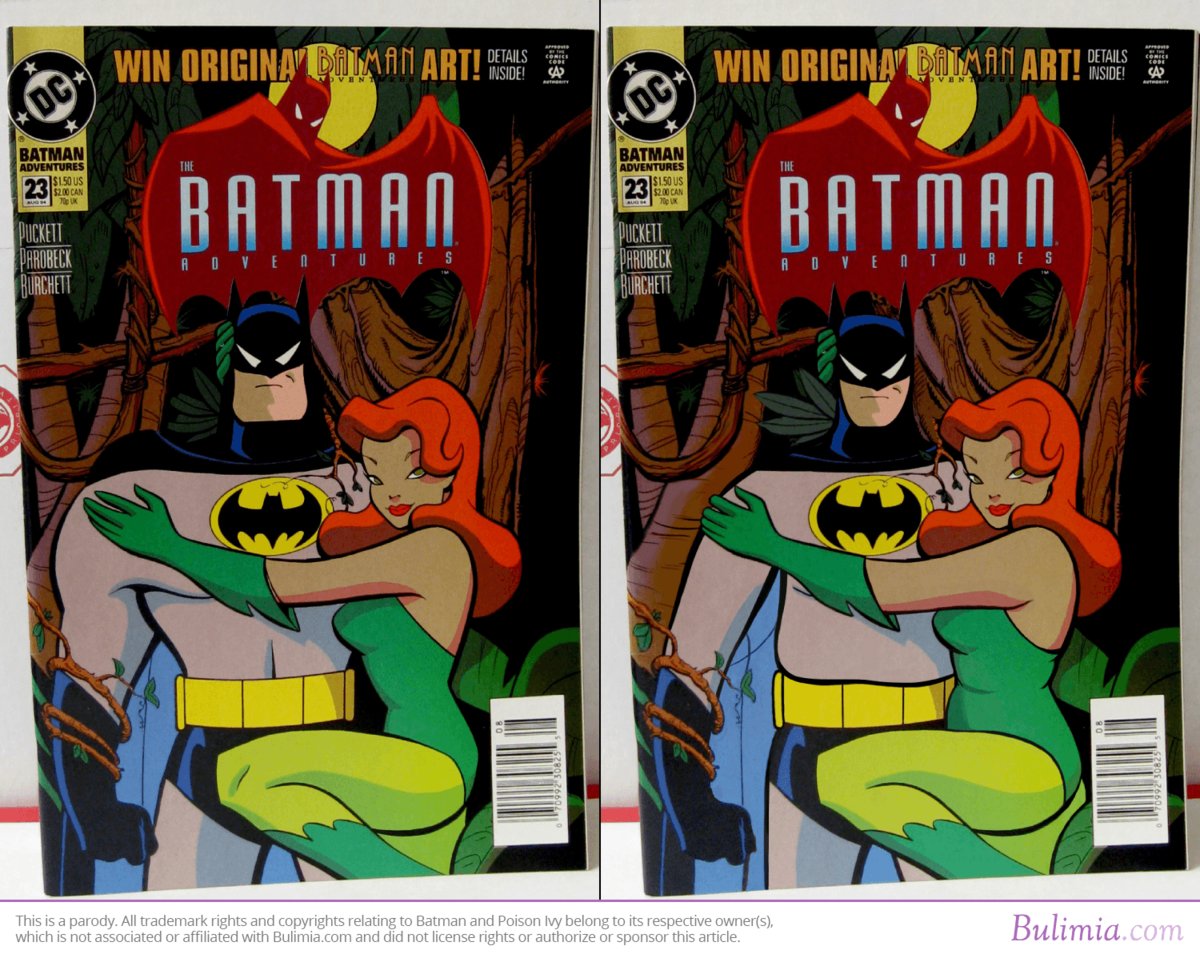

Idealized femininity is arguably more at odds with superhero power fantasies than idealized femininity. But even so, there's something to be said for the dumpier superhero men in Bulimia.com's versions. Look at this picture of Batman and Poison Ivy, for example.

Given her ability to make plants grow, and her connection to living things, the voluptuous earth-mother Ivy makes considerably more sense than the wispy super-model version. For his part, Batman ends up looking, well, a lot like Adam West, Bat-paunch and all. Since this is essentially a winking bondage image (note the branches wrapped around the Bat-arm), the less bulked-up Batman adds a nice touch of vulnerability and humor. Even his expression, sans that ridiculous jaw, shifts from impassive to disgruntled; the image, in every way, has more personality than the original.

Fans of the superhero genre sometimes defend the preposterous proportions on the grounds of fantasy; superheroes are meant to be unrealistic, and so should have unrealistic anatomy. But the Bulimia.com images suggest that (especially but not exclusively for women characters) the "idealized" body types often conflict with the narrative or aesthetic intent. Putting strict limits on bodies ends up restricting the kinds of stories you can tell, or the kinds of visual effects you can achieve.

Which is probably why, at places other than Marvel and DC—and sometimes even at Marvel and DC themselves—creators who want to tell even slightly different kinds of superhero stories will often use different kinds of superhero bodies. Ben 10 is just a regular kid; he's not particularly muscular or hyper-masculine, because the point of the show is to see that normal body change into all kinds of alien permutations (some with standard superheroic builds, some without).

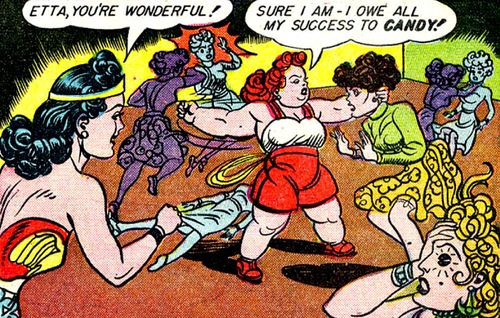

Sailor Moon is thin, but kid-thin, not fashion-model thin; the fantasy is about regular girls being awesome, rather than about imagining yourself as some ideal. That's the case with the shape-shifting Ms. Marvel as well. And there's always the wonderful Etta Candy, Wonder Woman's original side-kick, who was short and dumpy and thrashed bad guys with great enthusiasm and skill.

My 10-year-old son adored her when he read those original comics—though inevitably, humorless and unimaginative retcons have slimmed her down into unrecognizability.

Shuster's body-building fantasy has been influential, and will always be part of superherodom. But as Bulimia.com shows, there really isn't any reason that all heroes have to have the same body, and plenty of reasons to think that different bodies might lead to better stories, and to more adventurous dreams.